What 2020 Offers Us

November 24, 2020

Throughout 2020 I have been reminded frequently of the literature of Michael O’Brien. His work is often apocalyptic in nature (including the “Children of the Last Days” novels), so in the spring his cautionary tales of worldwide governance, questionable leadership and propaganda seemed apropos.

Yet as this year goes on, my attention has drifted past the external drama of anti-Christs and world domination and into the internal drama of O’Brien’s characters’ purification and holiness. The internal and external are juxtaposed powerfully in his literature.

Yet as this year goes on, my attention has drifted past the external drama of anti-Christs and world domination and into the internal drama of O’Brien’s characters’ purification and holiness. The internal and external are juxtaposed powerfully in his literature.

We tend to focus on the external drama that surrounds us, but the heart of the story is really the battle inside of each person to be conformed to Christ above all. In so many of O’Brien’s books, one or more characters undergo a fantastic transformation of detachment, suffering and an overpowering realization that Christ is the only reference point in one’s life.

The entire world has felt the struggle of 2020 on various levels. Certainly there has been the global pandemic, along with political battles, personal surprises and a fiercer polemic than in years past.

For many Catholics there has been the added experience of feeling disenfranchised from the places that felt the most secure. There has been confusion over some of Pope Francis’ remarks and  perplexity regarding various bishops’ approach to COVID in their dioceses. There have been conversations with friends that show disparate worldviews when there was formerly unity. There are arguments about voting in the two-party system or choosing a third party. Add to it all the months-long battle over masking, and we have a recipe for disharmony, fear, anger and alienation.

perplexity regarding various bishops’ approach to COVID in their dioceses. There have been conversations with friends that show disparate worldviews when there was formerly unity. There are arguments about voting in the two-party system or choosing a third party. Add to it all the months-long battle over masking, and we have a recipe for disharmony, fear, anger and alienation.

Why are we experiencing this? Why is the angst of social media jumping from the screen and the embittered com-boxes into our living rooms and church vestibules? Why are we in constant argument? Why do we fear confiding our opinions to friends in case of ridicule or further distance?

I wonder if we are all too easily caught up in the externals. There are many battles to watch (and a 24/7 news cycle pumping out a new headline every five minutes makes this even easier to consume full time). We are so absorbed in liturgical abuses, political jargon, whose sign is in whose yard, who stepped within my six feet orbit, what Pope Francis’ latest encyclical does or doesn’t do, that we have forgotten something enormously important — the “boring” things like prayer, sacrifice, detachment, ridicule, being misunderstood.

I wonder if we are all too easily caught up in the externals. There are many battles to watch (and a 24/7 news cycle pumping out a new headline every five minutes makes this even easier to consume full time). We are so absorbed in liturgical abuses, political jargon, whose sign is in whose yard, who stepped within my six feet orbit, what Pope Francis’ latest encyclical does or doesn’t do, that we have forgotten something enormously important — the “boring” things like prayer, sacrifice, detachment, ridicule, being misunderstood.

When G.K. Chesterton was asked what was wrong with the world, he opined with incredible brevity: “I am.”

Underneath the panoply of woes that we have become so fixated on, have we forgotten that what is most important is our own growth in holiness and ongoing purification? If we think that this task is wholly or even primarily bound up in who we voted for or courage in bucking the Church leadership’s sanctions during COVID, we have become far too easily distracted.

Confusion over governmental and Church leadership might be offering us opportunities for two virtues that are so vital (and yet so difficult and unwanted): Obedience and humility. Could it be that simply saying, “I obey” when we are told that public Masses are not available to us could bring us the interior purification we need but would otherwise resist? Might we find that sincerely asking what Pope Francis has to teach us could deflate our towering egos of superiority, bringing us a little closer to a Christ-like humility and submission?

Could God be using this tumultuous year as a “severe mercy” to offer us opportunities to suffer, grow and find renewed focus on what ultimately matters — “He must increase; I must decrease?” Is it even possible to unite ourselves with Christ on the cross without suffering?

Could God be using this tumultuous year as a “severe mercy” to offer us opportunities to suffer, grow and find renewed focus on what ultimately matters — “He must increase; I must decrease?” Is it even possible to unite ourselves with Christ on the cross without suffering?

I’ve heard complaints of priests who are focusing on things that are too “simple” for our times — things like prayer, virtue, charity toward others. I wonder, though, if this is precisely the time in which we all need to return to the “simple” things that are so challenging that we are constantly (and unwittingly) looking for ways to avoid them.

In the end, it doesn’t matter so much if I have internalized the latest critique of civilization so much as that I have embraced the cross. This could take the form of misunderstanding, alienation, or even detachment from the institutions that I previously thought of as my home (be that family, parish life, work, friend groups, etc.).

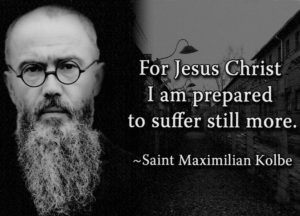

In the twentieth century we saw both the rise of two totalitarian regimes and the largest number of Christian martyrs in Church history. We can be quick to assume that the latter were made martyrs solely by the terrorization of Nazis and Communists. But before they could externally assent to die for Christ, there was an internal battle. They first had to die to self to be united to Jesus, ultimately giving up everything for him.

In the twentieth century we saw both the rise of two totalitarian regimes and the largest number of Christian martyrs in Church history. We can be quick to assume that the latter were made martyrs solely by the terrorization of Nazis and Communists. But before they could externally assent to die for Christ, there was an internal battle. They first had to die to self to be united to Jesus, ultimately giving up everything for him.

Inadvertently, these regimes could be said to have facilitated the growth in holiness of many subjected to their cruelty.

So, perhaps the emergence of totalitarian regimes gave these men and women an added impetus to embrace the cross. Terence Malik’s A Hidden Life  provides a glimpse of Bl. Franz Jägerstätter’s slow death to self before his eventual beheading. His fiat was fostered long before receiving a death sentence, but the Nazi regime could be said to have catapulted him into a deeper virtue.

provides a glimpse of Bl. Franz Jägerstätter’s slow death to self before his eventual beheading. His fiat was fostered long before receiving a death sentence, but the Nazi regime could be said to have catapulted him into a deeper virtue.

Several years ago when chaperoning a 150 mile vocations pilgrimage walk, one of the high school students approached me midway through the week with a confession to make. “I don’t feel like I’ve suffered much on this walk, even though I want to,” he said. “So I put a rock in my shoe to make myself  more uncomfortable. Do I have your permission to continue?”

more uncomfortable. Do I have your permission to continue?”

I was struck by his sincerity and humility in asking for permission but quickly was given the insight that perhaps he needed a different form of sacrifice. I told him he was not allowed to keep the rock in his shoe. “Sometimes the penance that God is asking of us, the one we don’t want, is precisely the one we most need,” I told him. “Accepting it causes us to grow even more than chosen sacrifices.”

This year we have been given quite the series of unchosen sufferings. Will we allow God to transform us through them, to grant us further purification through humility, obedience and charity? Or will we stubbornly seek what we think is best, thereby missing the cross that God is asking us to carry? The year isn’t over; we still have time to decide.

A Reflection by,

A Reflection by,

Emily Macke, Author of Called to be More,

ROOTED: Theology of the Body High School Curriculum

Share